- Home

- Christine Wunnicke

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura Page 2

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura Read online

Page 2

2

“Everyone has the same memories from childhood, Sensei,” declared the student. “We all remember the way our mother cleaned our ears, and the windmills, and the noises in the night.”

The student was walking two steps behind Dr. Shimamura, along a barely visible path between the rocks and the undergrowth. It was a hot summer day in the Shimane prefecture — July, 1891, according to the new calendar. Young Dr. Shimamura had recently completed his studies in Tokyo, where he had been the favorite pupil of Hajime Sakaki, professor of psychiatry.

“Please,” the student insisted, “don’t you agree, Sensei?”

Shimamura didn’t answer. He was long used to the student’s chatter, whose impoliteness bordered on mental aberration. What was his name? Surely Shimamura had known at one time, but later he forgot it, in fact it was astounding how completely he’d blocked it from his memory. And even back then he had never used it, but only referred to him as “student.”

They clambered through the underbrush. Shimamura carried his medical bag with stethoscope, gynecological speculum, Helmholtz ophthalmoscope, reflex hammer and Wilhelm Griesinger’s Mental Pathology, third edition, while the student lugged a large English duffle bag full of camera equipment. Shimamura wore a Norfolk jacket, straw hat and button boots. The student meanwhile had a loose peasant tunic that came down to just above the knees, and straw sandals that flapped as he walked.

“Do you also remember, Sensei, being told when you were little that if you left one shoe by itself it would turn into a shoe-ghost and come after you?” asked the student.

Three days earlier, in a moment of desperation, Shimamura had told him to borrow some local clothes and put them on, claiming this would help win the trust of the rural population. In truth he hoped that such undignified dress might put an end to the student’s babbling, but that didn’t happen. Now Shimamura was envious of all the air reaching the student’s body, especially around the neck. Shimamura’s own collar chafed and was so tight that whenever he turned his head he could feel his carotid pulse, and beads of sweat lined his slender moustache.

“And yet if everyone has the same childhood memories, isn't it astounding that we all turn out so different?” the student declared triumphantly.

Shimamura had no idea why Professor Sakaki had made him take as his assistant this particular medical student, who was probably no more than fifteen or sixteen years old. Nor could he say what the professor actually hoped to achieve with the entire expedition. “Go to Shimane,” Sakaki-sensei had said, “and study the annual epidemic of kitsune-tsuki. Examine every single afflicted woman and make a diagnosis. Pay particular attention to symptoms suggestive of nervous disorders.” So now Shimamura had spent days traipsing through the most miserable and forlorn districts of Shimane, where he’d examined a number of pitiful women said to be possessed by the fox demon, and had diagnosed the most annoying diseases (dipsomania, cretinism, an ovarian abscess rupturing into the rectum) — but he still had no idea what kind of trick Professor Sakaki was playing on him. “If no diagnosis is forthcoming,” his mentor had instructed, “then just write down ‘Fox’ hahaha.” Sakaki-sensei liked to joke. Perhaps the whole expedition was simply one big joke on the part of his professor.

The journey from Tokyo to Shimane took nearly two weeks. On foot. By litter carrier. In rickshaws with the student practically on his lap and constantly jabbering away. He was the scion of an ancient house whose family tree was worthy of awe. There were grandfathers and great uncles and great aunts who had died of eccentric, archaic diseases as soon as Japan opened its borders. There was also a four-hundred-year old war fan which one of the student’s ancestors had raised at the wrong moment, thereby causing the battle to be lost. The fan was preserved in the family shrine, a four hundred-year-old reminder of the value of humility. For two weeks the young student had related every single detail to Shun’ichi Shimamura in various rickshaws and inns, all the while smoking his pipe. Moreover, unlike Shimamura, he knew a lot about foxes. He counted the fox goddess Inari among his ancestors, and undoubtedly innumerable superstitious traditions had been passed down as family lore. He knew cases of fox possession stretching back four centuries, all of which befell the vassals of his powerful family. These, too, he related in great detail.

At home in Tokyo, Shimamura had worked on paralytic beri-beri and hereditary melancholia. He had been preparing for his trip to Europe which would take place as soon as he was granted an imperial stipend. He had also just gotten married to a doctor’s daughter, an unfriendly beanpole of a girl he couldn’t figure out. The young Shun’ichi Shimamura understood as much about women as he did about foxes. Nor did he fare particularly well with them, his female patients included. He was happy to report that the fair sex remained for the most part unafflicted by hereditary melancholy and paralytic beri-beri. Of course it was entirely possible that Sachiko, whom he had to marry because he was Professor Sakaki’s favorite student, was not so unfriendly by nature, but only around him. Was this perhaps the point of the professor’s practical joke? Meanwhile the student kept delivering the same lecture day in and day out: “It’s not a fox, Sensei, it’s a vixen! From woman to woman. All firmly in female hands!” Was Sakaki-sensei sitting in the Imperial University in Tokyo at his magnificent English desk beside the small statue of Hygieia merrily laughing up his sleeve because, of all people, Shun’ichi Shimamura was spending weeks in the scorching heat doing nothing but examining old-fashioned female insanity — with no benefit to science whatsoever?

“Would you just keep your mouth shut for once,” Shimamura told the student, who hadn’t actually been saying anything. Shimamura tripped over a dry root and stubbed his toes. “Over there’s a shady spot, Sensei,” the student proclaimed, pointing to the thin trunk of a thin tree with very few leaves. The student thrived and flourished in the heat. Shimamura suffered from low blood pressure and the summer dyspepsia that asthenics are prone to. He gratefully took advantage of the tiny bit of shade, where he squatted for a moment and closed his eyes. Then he studied the hand-drawn map provided by the director of the Matsue hospital, which for years had been responsible for Shimane women afflicted by fox-possession.

That day’s work focused on an area between Taotsu and Saiwa, where the director had marked three red fox signs, indicating that the fox had nested there three times. The unnamed location wasn’t very far, so Shimamura took a deep breath, squeezed his buttocks together to stabilize his blood pressure, and set off again.

On the way they were dogged by half-naked children scurrying out from under every rock and bush. Many carried smaller siblings on their backs, who slept or slobbered or chewed their little fists. They were probably all suffering from malnutrition of some sort. Whenever Shimamura glanced in their direction they scattered like a school of fish. The children showed no respect for the student, creeping up and tugging at him — and it wasn’t long before the first were clinging to him like barnacles to a boat. The student made faces at them. In his threadbare tunic he looked like their big brother. To shield his head from the sun he had tied on an old rag that made a mockery of any concept of hygiene. Despite all his annoying ways, the student was a good boy. Shimamura resolved to pay him a little more attention and perhaps teach him a thing or two about medicine, as long as the youth was in his charge.

They arrived at Taotsu, which they crossed in five minutes before again finding themselves in the pathless and pointless heat. By now the exorcists had joined the children; every day it was the same game. They, too, avoided Shimamura and worked on the student instead. There were already four of them: a limping monk, a little woman with magical banners, and two “receptacles.”

“Two receptacles have just joined us, Sensei!” the student announced with scarcely concealed enthusiasm.

The student knew how badly the so-called receptacles disgusted Shimamura, and Shimamura was not one to be easily disgusted — after all, he was a doctor.

Only yesterday he had abraded several skin lesions on a leprous female, simply as a respite from all the fox-women. But Shimamura really did feel a tremendous aversion toward the receptacles, and now he turned around and yelled. He screamed at the children and at the exorcists. He raised his fists, threatened to call the police, brandished his syringes — all to no avail. The children and exorcists made a big show of leaving only to sneak right back. And so it went day after day. Already the first receptacle was peeking over the student’s shoulder. “Shove off!” Shimamura bellowed. He felt a shiver despite the heat.

The so-called receptacles were the most pathetic exploiters of the fox-madness, and to group them with the exorcists would be an insult to the latter. The hospital director in Matsue had explained it all exactly. Every summer the most desperate lowlifes made the pilgrimage to Shimane to offer themselves as fox-receptacles. As fox-shelters. As fox-asylums. There were many names and each one was disgusting. The short form “receptacle” disgusted Shimamura the most. The ones who came to Shimane all wore a leash around the neck. Like a dog. Or a donkey. The leash said: Take me, I am your sacrifice. Oh how they filled Shimamura with loathing! When the fox demon left a possessed person — so Shimamura had learned — it was important not to leave him floating around homeless, and the receptacles made sure he had another place to go. They held soft tofu in their open mouths in order to attract the fox, the fox would come and sniff and lick and take the bait, and then would get swallowed — always with a lot of roaring and wrenching about. The hospital director described this transfer to Shimamura in great detail; just like the student, he enjoyed seeing how much the whole thing disgusted the know-it-all from Tokyo. The director also described what happened next to the receptacle or shelter or asylum: once the fox was inside, the receptacle succumbed to a puny, whimpering, drawn-out insanity and a very slow death characterized by a distinct odor. “We happen to have one lying out back. Don’t you want to have a look?” A special prayer was said over the body of the receptacle, in which the fox demon was now securely — or perhaps insecurely — enclosed, then the corpse was quickly tossed onto a weed fire or into the sea or a river or perhaps somewhere near a well with drinking water. (Dr. Shimamura came up with the last idea, as well as with the notion that particularly strong receptacles could accommodate several foxes before bloating up and ultimately exploding. By then he was dreaming of the receptacles, and in greater and greater detail, so deep was his disgust.)

Both of today’s receptacles, he ascertained, one male and one female, had surreptitiously untied their leashes, so the man in the straw hat wouldn’t guess their office. Now they walked sanctimoniously alongside the monk. Even they knew of Dr. Shimamura’s loathing and were taunting him.

Shimamura found himself searching for stones fit for throwing.

“There, up ahead!” the student shouted out in glee as he gave his pipe a triumphant knock to dump the ash.

The three red marks on the map were easy to spot in real life: well over a dozen receptacles were standing, lolling, sitting, and lying amid a whole forest of magical banners surrounding two huts so low they could have been stalls.

“May I take a photograph please, Sensei?” the student called out.

Shimamura fought to keep down the juices churning in his stomach.

“No, thank you,” said Dr. Shimamura. “As I have already explained to you we are conducting medical research, not ethnographic studies.”

The three fox signs marked by the hospital director from Matsue turned out to be an epileptic who fortunately presented a classic Jacksonian seizure within the first five minutes, her malingering sister, and an imbecilic neighbor who showed no other symptoms than her imbecility. The student was allowed to photograph the epileptic, but that didn’t satisfy him, since it was too dark inside the foul-smelling hut, and of course the seizure was long gone. So he proceeded to photograph the malingering sister as well as the imbecilic neighbor, albeit without first asking permission. He moved them both into the sunlight and had them pose in front of the banners, while Shimamura tried with great effort to coax a case history of the Jacksonian patient from her pitiful mother.

As always, Shimamura was unable to make any specific findings in the cases of alleged possession. As always, he was unable to follow the whining and whimpering of the country folk. And as always, the patients screamed bloody murder as soon as he attempted to examine them, and then, still howling, threw themselves on the student without restraint.

Along with the photography, receiving these desperate embraces had become the student’s second hobby. He wore the imprint of the filthy, tear-ridden girls’ faces on his chest like a ceremonial sash. Who could say if one of his accursed ancestors hadn’t laid healing hands on some lowly serfs four hundred years ago, and that perhaps some of that talent had been passed down to him. What’s more, he would whisper back and forth with all the sick people and their relatives — and clearly nothing concerning modern medicine. Once he went so far as to let a poor woman with an ovarian abscess spit on his hand, and then put on an earnest show of carrying it outside; Shimamura had watched him do it. He hadn’t questioned the student’s actions: he was too taken aback to forbid the young man such lunacy. But afterwards he lost three nights’ sleep wondering whether the student had paid one of the receptacles lurking outside to swallow the poor woman’s spittle. There was no doubt that the student was blithely offering his services as an exorcist, and Shimamura didn’t want to know anything about it. Inside the dark shack somewhere between Taotsu and Saiwa, where — instead of wiping away the urine the epileptic woman had abundantly dispensed — everyone was fervently praying, Shimamura came to the conclusion that he found all of it disgusting — the diseases, the people, medical science and superstition and the foxes and even Dr. Griesinger’s mental pathology.

For two weeks Shimamura and his student trekked across the scorching Shimane prefecture. There was no lack of foxes, but none of the patients displayed neurological symptoms, and even the psychiatric diagnoses remained vague. After many cases of tuberculosis, one of meningitis, three simple flus and all manner of nonspecific paralytic disorders, Shimamura had had enough and with no real justification he diagnosed one case of choreatic mania, simply because he liked the sound of the words, as well as one of gravidity psychosis.

Most of the people had nothing wrong with them. And while Shimamura looked the other way, the student healed them in his usual manner.

After two weeks Dr. Shimamura’s own condition had grown into full-blown neuro-asthenia, and his dyspepsia had become so explosive that for one whole day he thought he’d contracted cholera. The student had long since stopped following him on the paths and instead marched proudly in front, bending branches out of his master’s way and shooing off the receptacles so Shimamura wouldn’t have to. In the meantime he talked. And laughed. And smoked. And sang. Shimamura felt as though he’d grown old while the student had simply grown up, having matured into a man — although one clearly ill-served by German medical teachings. Shimamura had long ago given up teaching him anything. He couldn’t understand the student’s old songs any better than he could the fox patients’ moaning and groaning. Finally he decided to turn back.

“Now that you’ve done your duty exploring the rabble,” said the Matsue hospital director, when Shimamura tried to leave, “it’s time for you to see our little lady. Here you go. A new map. I’ve been saving her for last, just for you. Right here . . .” and he pointed to an enormous blood-red fox surrounded by a halo, emblazoned on a remote location beside a steep cliff. “Here you will find the blessed fishmonger’s daughter. Our celebrity. Your reward. The fox princess of Shimane.”

3

By Friday the weather was perfectly beautiful and since his fever hadn’t risen, Dr. Shimamura went for a walk with his wife.

Sachiko had never acquired a taste for this activity, even after so many years. She didn’t see the sense in running around outside

for the sake of one’s health instead of lying in bed and sparing one’s strength, which of course was already depleted if one was sick. Even in Kyoto she had always felt a little insulted whenever her husband extolled the benefits of fresh air: as if her own house had a bad smell — as if one had to resort to outdoor public spaces to clear the lungs. On occasion, when there was too much talk of walks, she set out enormous bouquets of flowers. Shimamura had never understood this silent criticism.

Sachiko Shimamura strode alongside her husband with an austere expression and a folded umbrella. There was nothing to see. It was too late for snow and too early for flowers and the castle was far too far away. Of course the temple did have a beautiful garden, but ever since Yukiko had taken to paying to get in, just so she could touch the miracle-working statue, the Shimamuras felt embarrassed and went out of their way to avoid the temple. The river wasn’t particularly beautiful, and it was almost as far as the castle. So the only thing left was a purposeless stroll. Sachiko cautiously placed her feet on the path that led from their somewhat remote house through the fields in the direction of town. With every third step she moved the umbrella forward, in an effort to conjure some concrete feeling along the way. After a while she managed to create a kind of rhythm that disposed of the seconds in an orderly manner, and she gave up her resistance. At least it isn’t raining, she thought, there’s no one coming we have to greet, and it is February, after all.

Shimamura mumbled something incomprehensible. She didn’t bother to ask, since it was undoubtedly a variation on the statement “the yields around here could definitely be improved.” He always said that when he took the path between the fields. All his life he’d spent his free moments thinking about important matters, without ever putting his thoughts into practice, and agronomy was one example. “Yes, dear,” said Sachiko.

At nearly sixty years she still stood very upright and proud. And she was tall, too, with a long neck and long arms she never let dangle alongside her body but always held neat and proper. She didn’t like having empty hands — hence the umbrella. Sachiko resembled her husband and her mother-in-law more than she did her own mother. When their families arranged the marriage this had been a constant theme: how well suited in height the bride and groom were. The fact is that no one could think of anything else to say. Sachiko wasn’t exactly dying to marry the young doctor. He seemed nervous and constantly engrossed in thought and during two weeks of courtship managed to break his glasses twice. She didn’t like that, but there were no significant objections and so she didn’t refuse.

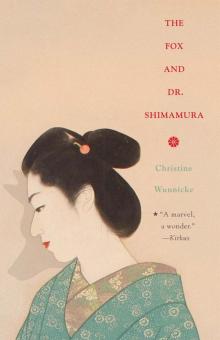

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura