- Home

- Christine Wunnicke

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura Page 6

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura Read online

Page 6

And so Shun’ichi Shimamura spent three days roaming through the Sorbonne and recruiting on behalf of the physiological psychologists. He had remarkable success. Everyone he approached chose to come. They clustered after him — students, teachers, staff. In fact so many people crowded all at once into the laboratory of Dr. Beaunis and Dr. Bidet to have their reaction times measured that the fall tachistoscope lost its calibration and the kymograph lost one of its legs. Test subjects had to be trained as measuring assistants or else the onslaught could never have been managed. Thanks to Shimamura more data was collected in three days than had been in an entire year — whenever he went walking down the corridor armed with his French sentence, people were lurking in wait, ready to pounce. Beaunis and Bidet invited him to dine in an elegant establishment. The next morning he woke up feeling insulted. He felt like a market crier. He doubted the relevance of reaction times. What was a neurologist, what was Japan supposed to do with healthy people watching little falling balls? Then it turned out that Dr. Bidet’s name was actually Binet. Perhaps his pince-nez was overly tight and constricted his nose when he spoke. But it was mostly this mishearing, which in the toilet of the Sorbonne had practically unleashed his inner beast, that caused Shun’ichi Shimamura to feel so out of sorts that he drew up a formal letter of resignation, which he had Sato translate into French and drop off at the laboratory for physiological psychology. The Imperial commission, he said in a roundabout manner, is indisposed to fund such a discipline.

From that point on Dr. Shimamura attended medical lectures. He didn’t understand them, and moreover he already knew the material: after all he was no longer a student. He drafted a general memorandum on the organization of medical study at the Sorbonne, which drifted somewhat into philosophical rumination.

He chose not to spend his free time with the law students. They were acquainted with a number of other Japanese in Paris who were studying law, with whom they passed many long, drunken evenings, mostly in the Cabaret of Hell — in addition to an establishment that evidently provided soy sauce. In the new Japan, the legal profession was to be modeled after French jurisprudence, which is why the city was swarming with so many budding lawyers. They gawped at the girls, concocted theories about them, and spread gossip from Tokyo which they kept receiving by letter. One enjoyed reading poems out loud that he then sent to Tokyo — verses that used elevated language to extol events there, for instance the birth of his dissertation advisor’s son and heir. Shimamura concluded that their company was also not part of his charge from the Imperial commission.

He sat in the Jardin du Luxembourg, eating his bread and cheese while yearning for tofu — all the more so after hearing the words soy sauce — and studied the German articles on memory strategies of blindfold chess players that Beaunis and his colleague had given him. The texts were based on correspondence between famous blindfold chess players and psychologists, as well as on laboratory experiments in which chess masters who were frequently engrossed in many games at once gave a running account as to how they stored the past moves inside their brains. The articles were difficult to decipher, which made the results seem more important. To Shimamura, who didn’t know how to play chess, they were hardly comprehensible. The blindfold chess players summoned pictures of chessboards they had never seen in real life, gleefully augmenting their games with phrases such as “bishop’s gambit.” With increasing anxiety, his tongue hallucinating about tofu, Shimamura studied these articles — forcing himself not to take them metaphorically, as a personal indictment, an insult to his own confused game. He stashed the bundle with Kiyo’s playthings in his briefcase and carried it wherever he went.

Shimamura went for many walks along the grand boulevards. He didn’t mind being seen holding his copy of Paris Monumental right in front of his nose. He traveled everywhere on foot. He went to the Eiffel Tower, crossed the Seine and systematically walked each ray emanating from the star of the Place de l’Étoile. On top of its magnificence, Paris was one grand cabinet of curiosities. Bit by bit he squandered a considerable amount of money to see everything he could, half out of interest, half out of a sense of duty, and occasionally as a self-punishment. He visited the wax museum, the Laterna Magica, the Diorama, the Panorama, the Kinetograph, and the morgue that housed the bodies recovered from the Seine. Then he went to a toy shop and bought toys — a locomotive, an astronomic gyroscope, alphabet dice in a little box, and a Noah’s ark with a collection of loose animals. He stuffed everything into his briefcase. Then he drank some coffee and crème de menthe and went back to the Diorama, because his ticket was still valid. There he stood for a long time in front of a scene of carnage based on a work by Émile Zola, where intricate lighting revealed different layers painted on the semi-transparent canvas.

The boulevards were teeming with women and dogs. The women spoke loudly, revealing teeth as well as gums, wore dresses that were full in back, and paraded in large, military steps. Their dogs were tiny, fluffy, and mostly white. They were called toutous. The women dragged them by the leash, pressed them to their bosoms, held them in gloved hands, under their arms, clamped in the crook of their elbows, swaddled in shawls like babies. Some of the toutous wore jewelry, some were dressed in uniforms. And all of them — toutous and women alike — wanted to make Dr. Shimamura’s acquaintance.

Apart from the small pink tongues of the toutous who licked him wherever they could manage, and which still haunted his dreams decades later, large stretches of this part of his stay in Paris remained foggy.

Shun’ichi Shimamura exuded a special magnetism that basically seemed to sweep aside the language barrier. Chinois and merci were all that were needed to set things in motion, and then there was no end to the reverberations. He had once had to accustom his mouth to German, and now Shimamura was also able to imitate French. He repeated words, adding oui or non at random, as he fended off the little dogs that were craning their necks to reach him or, when they were set down, trying to embrace his legs or attempting to mount his briefcase. Over and again time seemed to come to a standstill whenever a woman plunged into conversation with the Japanese doctor. In the Diorama, at the morgue, over crème de menthe and even on the other side of the Seine at the old fairgrounds where wild asses were on display, under streaming rain, united under a single umbrella, the world stopped for this or that Parisienne and the neurologist from the Far East. A conversation then ensued, so Shimamura understood, between something in him and something in her — a conversation that needed no French and no Japanese. And the toutous, when they escaped and climbed into his arms and licked him to their hearts’ content, whispered things in his ears that someone inside understood. Shimamura’s neck throbbed. His fever rose and fell, rose and fell, his memory frantically trying to reach back, so as not to have to take in the present: it recalled the word receptacle. Then it remembered the article about the consequences of sexual abstinence and clung to that for dear life.

Ultimately a heavyset, beautiful blonde with a lymphatic complexion took Shimamura along. Her toutou, a yellowish thing, ran ahead on a taut leash. Shimamura next found himself in a stone house, climbing a long, curved staircase, and then in a dark room full of ferns and fabric, a vast amount of warm fabric. He kept trying to figure out what the place was — a whorehouse, a rich family’s living room, a theater dressing room, a furniture warehouse? Then he gave up. On one of the pieces of furniture, a long mahogany chair, he peeled the blonde out of her dress, undoing her bodice with his physician’s fingers. “How could you . . .” said Shimamura’s brain, taking its leave. There was a moment of impetuosity, some scuffling, drastic, not nice. Whatever it was struggled. Whatever it was conversed. There were tears. The blonde woman’s skin was streaked with deep red wheals, as if she’d been swiped by a bear. “Dermographism,” said Shimamura’s brain, which had reappeared. And for a moment was ashamed. Then it disappeared again. And everything started all over. A stem on his glasses broke and this time when someone howled it wa

s no longer clear who.

The toutou watched. It sat there quietly and watched, its forepaws neatly parallel, with its tiny, yellowed face.

When it was all over they rushed apart without saying a word.

That same evening, after he had taken his eyeglasses to an optician who repaired them on the spot, Shun’ichi Shimamura had the idea of taking the tram. He rode back across the Seine. Then he boarded a different car. Following in the wake of the women and dogs, subduing his hallucinations, Dr. Shimamura rode many different trams: St. Michel, Port Royal, St. Marcel. There he climbed out and found a splendid stone structure with a tall cupola. That was the Hôpital de la Salpêtrière, a women’s asylum with five thousand beds. In Tokyo hardly a day had passed without Professor Sakaki mentioning its name.

8

“In our house,” said Sachiko Shimamura, “everyone has gotten used to hiding things, mostly under the floor, and everyone knows where the things are hidden and fingers them in secret.”

She was sitting on the west porch with her mother and stepmother. Because it was much too warm for the beginning of March they were imbibing soft drinks, one “strawberry” and two “original.” Sachiko, Hanako and Yukiko had performed the requisite ceremony — pounding the stopper inside with their fist and freeing the glass marble which then danced with every swallow — and now they were drinking out of the bottle like young girls.

“Taking the trouble to hide things makes no sense,” said Sachiko, “at least not for us, although with Shimamura the habit is probably already too engrained.”

“These days I can’t find anything as it is,” said Yukiko.

They all laughed and drank. The three marbles clinked.

“What a beautiful summer sound.”

“Ah yes.”

“Ah yes.”

Outside by the clothes pole where she had hung out the bed linens, Sei was singing her song about Uji and Kei. Sachiko had forbidden her to sing, but had then changed her mind and encouraged her to sing whenever she wanted to. Sachiko Shimamura, the most patient person in the world, had recently become somewhat impatient and her moods were now a little fickle. Sei’s sweet and slightly eerie voice wafted over as she sang the only song she knew.

“Hanako,” said Sachiko, smiling, “you recently wrote in Shimamura’s biography that the song about Uji and Kei was an important part of his childhood. Then Shimamura dug out your pages from under the floor of the north room, while you sat in the southern room reading your novel, and now he believes that ‘Uji and Kei’ were an important part of his childhood. But in reality there is no such song.”

“That’s too complicated for me,” declared Yukiko. “May I please be excused?”

“How do you know what he believes?” asked Hanako.

“He’s so reluctant to leave his own room that unless he was looking for some information he wouldn’t keep digging out your pages from under that floor.”

“May I please be excused?” Yukiko repeated stubbornly.

“Every winter you fix up the fox girl’s toys that he hides behind the Charcot,” said Hanako gently to Sachiko. “You’ve been doing it for years. You buy a new toy and carefully make it look broken and dirty and then you stick it in his bookcase in place of the old toy. That must put him on edge. He can hardly guess what’s going on. What a strange experiment.”

“Of course, Mother, you are excused,” Sachiko said to Yukiko. “Go and have a nap.”

Yukiko sighed. She let her marble clatter without drinking. Now she felt obliged to stay, even if that meant suffering for a few more hours; now she wouldn’t dream of taking a nap.

“As long as he’s on edge,” said Sachiko, “he won’t lose his will to live. You must know that better than anyone. You keep rewriting his biography just because you know he keeps reading it. No one else would go to such trouble, especially not someone for whom writing does not come easy. Besides, it’s interesting, isn’t it? From a medical point of view.”

“I’m not a doctor,” said Hanako.

“In some way we all are. Being a doctor is contagious.”

“Perish the thought!” Yukiko rubbed her hands together. “Praised be the eternal light.”

“So how long will it be before he realizes something’s not right with the toy?” asked Hanako. “Not that I really care . . .”

“I don’t exactly watch him,” said Sachiko.

“You switch things around, don’t you, one year it’s a monkey in the bundle and next it’s a princess.”

“Monkeys, princesses, little frogs,” said Sachiko. “The rest I replace one-to-one. And every other year I put in a pinwheel.”

“That sure is complicated,” warbled Yukiko, who suddenly seemed to think the whole business was a lot of fun. Sachiko, Hanako and Yukiko often spent hours and days in such conversations that led nowhere and which no one understood. They had nothing better to pass the time.

Sachiko and Hanako wondered in silence how to measure the progress and intensity of Shimamura’s reaction to the swapped playthings, without being too blatant. The fact that officially no one but he knew there were toys hidden behind the Charcot posed a problem. And who wanted to spend all day spying through a peephole? Besides, how could a peephole be installed in such a thick door? And who could look inside Shimamura’s head and who would want to? “Diegedankensindfrei” Sachiko quoted the German folk song about freedom of thought — another phrase that wouldn’t get her very far as a tourist in Germany — to which Hanako simply said: “You silly girl.” Both women gently shook their heads. Yukiko meanwhile had conjured a bag of konpeito candy from out of her sleeve and was eating it piecemeal without offering them any.

“You keep all your estate papers under the floor of the south room,” Hanako said to Sachiko. “In Stepfather’s pharmacology book.”

“That’s right. And you study them in secret.”

Hanako and Sachiko laughed. Yukiko stuck a hailstone-sized candy in the one spot in her mouth where two molars still connected, and cracked it open. Then she called out “I hide everything in the west! Right here!” And she banged behind her on the planks of the veranda.

“Money,” said Hanako, “slips of paper from the temple, and scopolamine. We look at it every day.”

Now all three laughed.

“Who hides things in the east?” asked Hanako.

“Sei?”

They all laughed, and all said “Poor Sei.” They sat for a while in silence, without moving, and enjoyed the sound of the wind and the song wafting over. Then Sachiko doled out a new round of soft drinks and came up with another subject for a lengthy conversation.

9

Jean-Martin Charcot, who ruled over the women’s asylum La Salpêtrière, was the most famous neurologist in the world and probably also the most famous Parisian — there really was no limit to his renown. He looked like a Roman emperor, spoke ten languages, including German, and with a charming smile was delighted to accept all of Shimamura’s woodcuts from Nagasaki as soon as he laid eyes on them. He explained they would enrich the planned second volume of his book Les Démoniaques dans l’art, which proved also to lay readers that female insanity and so-called possession were a universal phenomenon, historically as well as geographically. Then he quickly changed the subject.

Dr. Shimamura couldn’t say why he found himself sitting at the table of Professor Charcot like an old family friend, just days after he finally discovered the asylum. He vaguely remembered a whole swarm of female patients buzzing around him the minute he stepped into the Salpêtrière, and that this swarm had immediately transported him to Charcot like bees carrying a queen.

Meanwhile Charcot’s assistants had been swarming around the master. And he had been very busy, because every patient he visited on his evening rounds displayed some neurological disorder as soon as he approached the bed. The patients who were escorting Shimamura likewise

displayed a variety of symptoms the moment they spotted Charcot. The result was a great hullabaloo. And in the middle of all this noise, among all the fluttering hair and flapping shirts, Charcot caught sight of Shimamura. And something happened. A spark leapt between them.

(Later, in the many versions of his memoirs which he wrote in German so Sachiko couldn’t read them, he had to replace this very apt expression with “sympathy arose” even though it didn’t accurately capture the moment. But Shimamura had so often made a mistake while writing the sentence and discovered that he’d put down “fox” instead of “spark” that he gave up on the latter).

Whatever it was that happened when Charcot caught sight of Shimamura and Shimamura caught sight of Charcot — it was there to stay. The shrine of neurology opened its doors, and the young man on the imperial stipend was soon sitting in Charcot’s mansion on the Boulevard Saint-Germain, poking at truffled grouse and discussing the simple dignity of Noh theater, especially with the head of the household, who had been impressed by what he had seen at the Exposition Universelle.

Long before he fully understood the Salpêtrière, one thing was clear to Shimamura: Professor Charcot was quite fond of animals. He had a sign posted at the entrance to the clinic letting it be known that dogs were not experimented on there. The decapitation laboratory at the Sorbonne was a thorn in his side. Even guinea pigs elicited his sympathy. He owned a pet monkey who answered to the name Rosalie and was allowed free rein. He would stop beside a draft horse and speak to it consolingly. Shimamura’s woodcuts set off a long tirade against the horrors of fox hunting, in which he was completely oblivious to the fact that his index finger was resting the entire time on a half-animal penis protruding disembodied from the folds of a kimono. Shimamura had to suppress a laugh. Then he was moved. Then he was hungry. Then he had a headache. Then he felt a chill. He took a deep breath. He still did not like looking at the foxes.

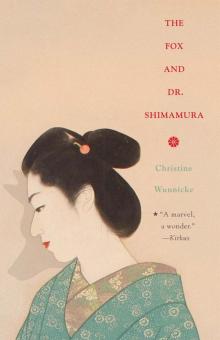

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura