- Home

- Christine Wunnicke

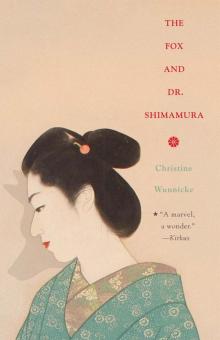

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura Page 8

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura Read online

Page 8

Thinking about Charcot always made him smile. His students at the Kyoto Prefectural Medical College had made a sport of suddenly saying “Charcot” whenever Professor Shimamura walked past, because it never failed to elicit a smile — the only smile in his repertoire: it even lifted his moustache. “Charcot, Charcot,” the students would exclaim — and even in the middle of a lecture this would force a smile from Shimamura — Shimamura the most lenient professor, the mildest examiner, the most gentle human being — and he would interrupt himself and address the class with “Eh, well, what about Charcot?” Then he would have one student recite Charcot’s neurological triad for multiple sclerosis: nystagmus, intention tremor, and dysarthria, although the students could never figure out what was so smile-worthy about that.

“I can never remember exactly what toys are in this bundle,” Shimamura muttered to himself. “There’s bound to be a reason for that and I ought to make a note.” He reached into the pocket of his robe and took out the notebook where he jotted occasional ideas for the memory project. The notebook seemed as unfamiliar as the toy. Had it always been brown? He stuck it back in his pocket.

Then he laid the toys on the crumpled cloth, which he carefully tied back into a bundle and crammed onto the shelf. “There you go, you old arthritic liar, you’ve been dead now for a long time,” Shimamura said to Volume Six of the French Charcot, sliding him back into the row of books so that everything was nice and tidy.

Ever since Shimamura, confused and flattered, had assured Charcot that he would be happy to assist with a lecture at any time, the professor had once again made himself scarce. And once again Shimamura saw himself running up and down the Salpêtrière behind Babinski, chasing after information. “Look it up, it’s all in the books,” said Dr. Babinski, who seemed unable to comprehend that someone might not understand French. The Salpêtrière was packed with Charcot’s works; the myriad volumes in multiple copies took up yards and yards of bookshelves. Was it the will of the Imperial Commission that Shimamura learn French? He kept studying the books from the outside as well as from the inside, without result. “What is your therapeutic practice?” he asked Babinski more than once and Babinski answered “Rest, laudanum, cold water, look it up.” And with that he sighed, as if only a philistine, only a simpleminded oriental would want to destroy the artistic masterpiece of a grande hystérie.

The days until Tuesday, when Charcot’s next lecture was scheduled, passed slowly. With a tinge of rebellion Shimamura assisted Dr. Binet, who without Charcot’s knowledge was measuring reaction times of the female patients with a pocket tachistoscope. His free time he spent going up and down the boulevards. He would turn up his collar, pull his hat down into his face and walk quickly ahead, bent forward as though fighting a wind, in order to avoid encounters. Half aghast and half with a diagnostic eye he observed the swaying silhouettes of the ladies, their martial steps, their long, soft arms slung around purchases, umbrellas and little dogs, the arabesques of their scarves, their hats. At home, when he ventured out of his room, the law students called out “hisuterii” and made all sorts of mischief. If only he had never mentioned the word. He went with them to the Cabaret of Hell and got drunk.

At last it was Tuesday.

Running a temperature of over 100 degrees, Shun’ichi Shimamura made his way to the Salpêtrière. The tram was packed. Hackneys were pulling up to the gate. People were pushing into the entrance hall. So at last they have a visiting day, Shimamura thought, somewhat leery. He went to report to Dr. Tourette as he had been instructed.

“Today is your day,” Tourette snapped. He didn’t invite Shimamura into his room and instead maneuvered him past the crowd, then guided him through a narrow door into a dark hallway where some old equipment was stored: a kind of padded harness with straps and screws and a threaded axle, an entire arsenal of the devices. “Special passage to stage,” said Tourette. “Ovary compressors. Discarded. Unreliable stimulus. Just like you.”

“Pardon?” said Shimamura.

The corridor led directly to the main auditorium and a rear entrance onto the stage.

“Rabbit,” said Tourette. “Hat. Not everyone wants to see beforehand. Do we understand? Thank you.”

“I . . . pardon?” asked Shimamura.

Without a word, Tourette shoved him onto a stool located behind a masking screen at the edge of the stage. “Don’t move. Until Charcot. Or I. Thank you.” And he was off.

Shimamura peered through a crack between two panels of the screen. The amphitheater was large, with considerable brown wood and pear-shaped lamps. The rows were already well filled. Men in black, men in gray, ladies with feathered hats, once more the figures in the outmoded robes who Shimamura thought were poets, Dr. Beaunis with some students and the people from the guinea pig lab, Charcot’s daughter with her husband, and very far in the front a large woman in moss green next to a boy in a sailor suit. Shimamura understood that neurology was being taught to the public, and suppressed his own opinion on the matter. The child in the sailor suit seemed familiar. Perhaps Shimamura had seen him in the morgue with the bodies from the Seine. Maybe the green lady wasn’t his mother but his teacher. Was that important? Wise? Did Japan have to know that? Shimamura couldn’t concentrate on any of this because his overheated brain kept droning the words “rabbit” and “hat” and nothing else. But he found no association, no saying, no image, no allegory. The question of what Shimamura had in common with an ovary compressor paled against this problem. Rabbit? Hat? Was Tourette’s German so atrocious? Or was he simply trying to annoy Shimamura? Ever since Charcot had given him a personal demonstration of the stages of hysteria, Tourette had treated the guest with scarcely concealed disdain.

More and more people crowded into the hall. All the seats were long since taken. Is it possible Charcot was charging an entrance fee? Did he divvy up the proceeds among his patients, so they could buy frills and trinkets, the compassionate Professor Charcot? For Emperor and Fatherland, Shimamura thought crossly. And then it all began.

Charcot spoke a few words of welcome. Then Babinski led in a little man suffering from Parkinson’s disease. The man was obliged to shuffle around on the dais and manifest the major symptoms. Charcot brought a device for measuring the tremors. Finally Dr. Bourneville applied small electrical shocks to his back and chest. The little man was so embarrassed that he didn’t react to anything. He was supposed to say something, but he didn’t. Charcot’s charms were wasted on the sick man. The audience was audibly bored. The boy in the sailor suit tried to chew his nails and the green woman gave him a slap. Then she took some notes. Perhaps she was studying neurology here in secret, Shimamura suddenly thought, in order to commit a crime. He ruminated on this a while, but no crime occurred to him that required the study of neurology. He was so preoccupied with that thought that he missed the first case of hysteria. It wasn’t until the second case that he again peered through the crack.

The woman was already half naked. The audience sighed. As expected, the focus was on hysterogenic zones. The neck. The lips. The palms. The upper abdomen. Next would have come the lower abdomen, but this was not demonstrated, only explained. Soon it was time for number three, a tender young thing with chestnut-brown braids that Charcot gently brushed aside to stimulate the earlobes, first with feathers and then with needles. Even the nurse who helped with the undergarments was pretty, the only pretty nurse in the whole damned Salpêtrière. Before he knew it the fourth patient was on stage, trembling. With a glassy gaze she stretched out her long, beautiful tongue toward a tuning fork. Oh what an ape-show of anguished sexuality, Shimamura formulated carefully in his mind, in German. He felt a sense of elation. The longer he was in France, the better his German became. Suddenly the entire linguistic beauty from all the Reclam classics he had read as a student came to a creative coalescence inside his head. Gotthelf. Paul Heyse. Immermann. The sailor boy looked delighted as he stuck three fingers deep inside his mouth. The g

reen woman was writing. Was she from the newspaper? A poet? Each one of the female patients swooned onto Babinski’s broad chest, while Charcot was busy with their zones and Bourneville was handing off one apparatus after the next, and Tourette watched, all the while moving his lips. Perhaps he was hissing “foutu cochon” like the marquise whose tics had served as godmother to the famous malady that bore his name. The audience applauded as the nurse led the fourth hysterical patient away, and Tourette popped out of the floor right next to Shimamura’s footstool, like the devil in a theater.

“Get ready. You’re next,” he said, and Shimamura spun around, taken aback by Tourette’s use of the familiar Du. “And by the way, read the books,” Tourette whispered with a sneer, “like Babinski says – perhaps German better?” His unpleasant mouth cracked an unpleasant grin. “That guest from Vienna, Freud. All lectures in German.” Tourette spat these words out like spoiled food. He seemed to dislike the guest from Vienna as much as he did the guest from Tokyo. “So why are you telling me that only now . . .” whispered Shimamura. Then came a burst of applause, and Tourette again materialized in the center of the stage. “Pff,” said Shimamura into the crack in the screen. He could have been reading for weeks. Understanding everything for weeks. He sighed. The applause swelled louder and louder, then suddenly broke off and gave way to a reverential silence.

A new patient had entered. Proud, heavy, shy, and insane, she stood in front of Charcot. Babinski and Tourette watched her furtively from both sides, as though she were a precious vase that might get knocked over at any moment. She was no longer young and hadn’t been groomed or laced up, and her disheveled hair was thinning on top. She stood there in bare feet, her corpulent body draped with a sheet starched as stiff as a board. Otherwise she was wearing nothing. She swayed gently as though she were dizzy. With every movement the sheet wrinkled into geometric prisms. Charcot addressed the audience. He, too, swayed slightly, as though he and the afflicted woman were standing on board a ship. I don’t want to do this, thought Shimamura. I don’t want to go out there. Bourneville had stepped up and was passing a Helmholtz ophthalmoscope back and forth in front of the patient’s face, chanting numbers as he did. Charcot looked intensely in the other direction. Shimamura stared at the ophthalmoscope. Mesmerism? Hypnotism? Was he serious? Oh pfui, Professor Charcot. Two tears rolled down the patient’s cheeks, and then her eyes slowly closed. Rabbit . . . hat . . . kept droning inside Shimamura’s brain. The patient was long since cataleptic, her hands folded into the sheet, her blue eyes like glass. Shimamura tried to swallow but couldn’t. Bourneville slipped the ophthalmoscope back into his vest pocket and stepped away to join Babinski and Tourette.

Charcot spoke to the audience as he gently pulled the patient’s right arm out of the fabric and lifted it, then bent it and shaped it into an expressive pose. The ship on which they were standing was no longer rocking, it had docked and now Charcot’s companion waved weakly over the railing. He touched her chin. Her head moved to the side. He reached into the sheet. Her body folded over at the waist. Charcot spoke, and as he did he tenderly bent each finger of the waving hand — but backwards. Her hands were broad and pale, with inflamed nail beds. Under Charcot’s touch, one hand was transformed into some sort of bizarre growth that did not belong on a human arm. “Bienvenue Nagasaki,” Charcot purred. And then Shimamura was standing in the middle of the podium with no idea how he had arrived there.

The blue eyes of the somnambulant woman were peering straight through him. Her lips were slightly open. He could feel and smell her breath, a gentle whiff of lemon balm tea. Then he felt Charcot’s index finger in his back. He walked slowly backwards. The patient came too, swaying, one little step at a time, like a caterpillar lifting itself at the edge of a leaf, feeling its way. The deformed hand relaxed. She fished an umbrella out of the air, which she used to ward off the snow. Her head, too heavy for her neck, jerked and pecked like a pigeon’s. She shielded herself against the sun. Against the snow. Against the sun. Then the umbrella slipped out of her hands and she stood still, a white triangle with asymmetries as complicated as a woman’s soul, as complex as the love of the bamboo princess who sinks at the feet of the emperor under a full moon. And there, sinking down, she kowtowed on the floor. Shimamura, his neck throbbing, backed off. The bamboo princess, swathed in her moonlit hair, hid her face in a sleeve, then in a fan. Sounds came from her mouth, first a cooing, then a gasping, then words. Her hair grazed Shimamura’s shoes, and then she was drawn upward as though by threads; she reared up, bent over, and sang. A foreign language that Shimamura understood. Life, a turning wheel! Life, the wheel of pain! She stretched out her arms. The spirit of the Lady Rokujo, trapped in the body of the Lady Aoi. Life, fleeting as foam, broken on the wheel of those reborn! A voice of lamentation, up and down, warbling, roaring, then a cry. Brittle, brittle is life! The black hole of her mouth. Many spirits were trapped in the body of Lady Aoi; one person alone could not have all these voices. I am a shadow! Now she plucked away at an instrument. Shimamura saw the smooth wood, the strings, the crescent holes in the sound board, the charms dangling from the tuning pegs. He dug his fingernails into his palms. The rail separating the stage from the auditorium pressed against his lower back. It was impossible to retreat any further. Brittle! Brittle! Leaf of the banana tree! She bowed deeply and the instrument blew away from her hands. Now she was once again crawling and feeling her way. Shimamura pressed against the rail. Their eyes met. She was awake, wide awake. Was that a smile? With two fingers she cautiously creased new pleats of madness in her stiff white garment. Then she sank lifelessly to the floor. And was reborn. There she stood, fresh and pure and embarrassed, a little girl in a spring dress fumbling with her sash who didn’t know what to do with her fan. Or was she holding a small cup? A flower? A stuffed monkey? “Charcot,” Shimamura whispered. He no longer saw the famous professor. Instead he saw plum blossoms in the first night of their flowering. And she was feeling her way through the trees. So young. So sweet. Was she blind? She reached out into empty space. Her puppetlike joints clicked gently. There, the Umeda bridge . . . The rods manipulating Shimamura’s paper arms slowly rose. It is the bridge, beloved, that the magpies laid across the milky way . . . “Charcot!” Shimamura whimpered. Here in the Tenjin woods is where we’ll die. Namu amida butsu. Shimamura withdrew the dagger from her bosom. Her body, a wisp, a trace — lifeless she sank at his feet. Husband and wife for all eternity. And he slit his throat. The audience went wild.

“Thank you,” said Professor Charcot. Then Tourette took over. He shoved Shimamura across the stage and back behind the screen. Bourneville and Babinski hurried to help the patient. A wet washcloth, a vial of smelling salts were discreetly put into service. Something was still clicking. Shimamura realized it was Tourette snapping his fingers right in his face. “How dare you!” whispered Shimamura. He plopped onto his stool. And there he sat, perfectly still, as Charcot recited a long epilogue and the audience went silent, then applauded, stood up, chatting as they slowly left the room, as Tourette slinked away and Babinski marched past, as Bourneville secured his apparatus with the help of an assistant, as someone came with a broom to sweep the floor. Then he stood up. He was now alone in the grand auditorium of the Salpêtrière. He found the hallway with the ovary compressors and followed it, still a bit unsure of himself, but resolute and awake. He made his way to Charcot’s consulting room. Patients ducked out of his way. A staircase, a corridor. Without knocking he stepped into the professor’s room, and there was Charcot, still somewhat flushed and breathless, while his assistants hovered around him, engaged in an animated discussion. The blonde patient had had her hair tied up and was now wearing a green blanket over her sheet. She was leaning on Charcot’s desk, still quaking like an aspen and talking with Babinski.

“Charcot,” Shimamura hissed. Everyone turned to face him. The patient curtsied, like a child confronted by a scary stranger. “Thank you, thank you!” Charcot called out, grabbing bo

th of Shimamura’s hands and giving them a friendly squeeze.

“You showed her my woodcuts,” said Shimamura. “You were with her at the Exposition. You are a deceiver. A swindler. An impostor, a rascal, a lying rogue, a charlatan.” An entire German thesaurus came gushing out of Shimamura’s narrow lips. “You are a disgrace,” said Shimamura, “to the entire neurological profession. You . . . you . . . showman!” His neck was throbbing. The thesaurus ran out. “Scoundrel!” hissed Shun’ichi Shimamura, then bowed deeply and rose up and began to howl. The howl was the last thing he heard.

When he awoke he was lying on the floor with his shirt in tatters and his head nestled in the blonde patient’s lap. Charcot, Babinski, Tourette and half a dozen other doctors were bending over him. Charcot’s shirt was also torn. A bruise was forming over his left eye. He was beaming. The patient was stroking Shimamura’s hair, which was standing on end.

The consultation room was devastated. Potted plants had been uprooted. The floor was littered with books, paper, writing utensils, percussion hammers. Chairs had been overturned and a glass cabinet had been shattered.

Charcot and his patient calmly helped Shimamura to his feet and led him to the chaise longue. Babinski brought water. Tourette — pale with disgust — handed him a handkerchief.

“Better? Better? Better?” Charcot asked, concerned. He was still beaming.

“Better? Better?” aped the blonde patient.

Shimamura nodded. He tasted blood in his mouth. He swallowed and drank some water. Charcot had again gripped his hand and was stroking one of his forearms; the blonde patient stroked the other.

“My dear colleague,” said Charcot, beaming so much it lit up the room. “That was the most well-ordered, most beautiful, detailed grande hystérie I have ever witnessed in a man. You have no idea how important that is. For neurology. For me. For everyone — whether lay person or physician. For all women in this bigoted world! For years I have been fighting the prejudice that the stronger sex is immune to this disease. I thank you. As a colleague. As a comrade-in-arms. Together we will prove to the world — ”

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura

The Fox and Dr. Shimamura